CACHE Challenge

Recently a team of us from Newcastle University were fortunate enough to enter the second Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-Finding Experiments (CACHE) Challenge. The full team comprised: Ben Cree, Rachael Pirie, Mat Bieniek, Josh Horton and Daniel Cole (computational chemistry), Roly Armstrong and Kate Harris (medicinal chemistry) and Natalie Tatum (structural biology).

What is CACHE?

The CACHE challenges are a set of prospective benchmarking exercises of computational hit-finding predictions, organised by Conscience in collaboration with researchers at the Structural Genomics Consortium. Every few months an open hit finding exercise is advertised with the goal of identifying new chemical starting points against biologically relevant targets. By purchasing and testing the compounds, the organisers are able to benchmark the effectiveness of new computational methods. Each challenge has two hit finding cycles to enable elaboration of first round hits.

More details may be found online, at the Conscience website, and in this review paper.

We are hugely grateful to the CACHE organisers for allowing us to enter, and for the experimental data shown here (any errors are our own!).

What is the target in challenge 2?

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus responsible for the 2020 global pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 has 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs) that are integral for various processes related to transcription and replication of the virus. The RNA binding site of the NSP13 helicase is a particularly promising drug target due to the highly conserved nature of the site across coronaviruses. See the CACHE challenge page for more details.

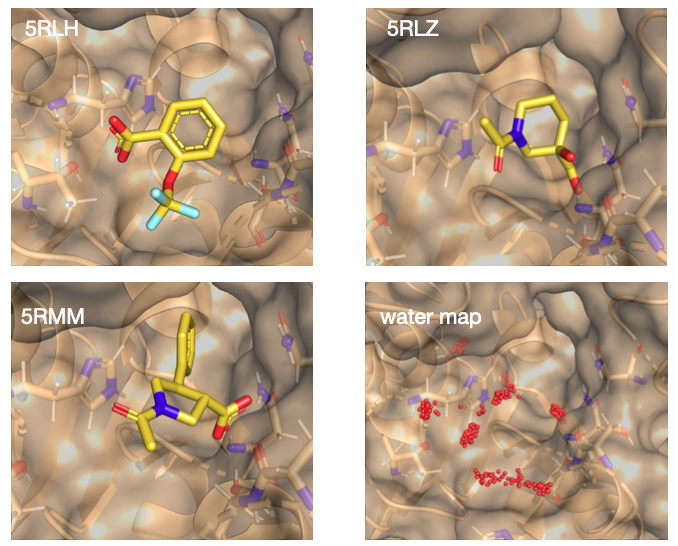

The crystal structure of NSP13 has been determined in complex with fragments bound in the evolutionary conserved RNA-binding site (5RLH, 5RLZ, and 5RMM). We judged that a fourth fragment (5RML) was too far from the others to be linked or merged.

In addition, we used structural waters collected from around 60 structures of NSP13 close to the initial fragments, producing a water map that was useful for identifying potential polar contacts and additional pockets.

Crystallographic bound fragments and water map

Design Strategy

The basis for our design approach was fragment growing, pursued using our open-source FEgrow software package. For a given ligand core and growth vector, FEgrow allows the user to grow and score functional groups in the context of the protein binding pocket. FEgrow enumerates the bioactive conformations of the grown functional group, discards those that clash with the protein, and optimises the remainder using hybrid machine learning / molecular mechanics potential energy functions. In particular, the ANI machine learning potential is used to describe the energetics of the ligand, which is significantly more reliable than the use of molecular mechanics force fields that are commonly used for refinement. Low energy structures are scored using the gnina convolutional neural network scoring function. Optionally, output structures are usually suitable for input to free energy calculations, but in round 1 due to time pressures we relied on the docking score alone.

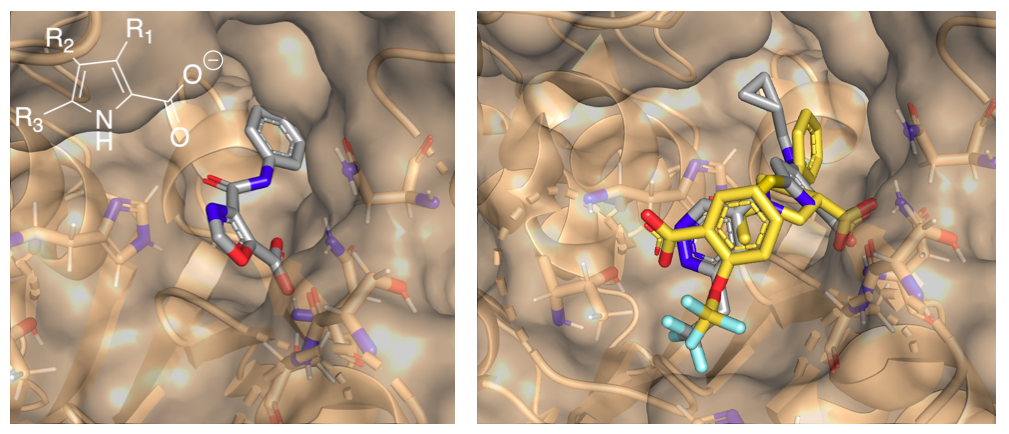

Fragments 5RMM and 5RLZ share a common binding mode with a carboxylate group occupying one of the identified water clusters. A 5-membered ring seemed to give three promising growth vectors (see Figure below), and so we used FEgrow to investigate a range of linkers and functional groups at the R1, R2 and R3 positions, as well as various 5-membered rings and carboxylic acid bioisosteres.

In particular, the R1 pocket, which is occupied by a phenyl group in 5RMM, seemed to give opportunities for growth, and the R3 vector allowed us to merge designs with the 5RLH fragment. This led to designs like the one shown below (right), which recapitulates many of the fragment interactions and has a good gnina docking score (1.4 μM).

(left) Example compound design and (inset) definition of growth vectors. (right) Example 1.4 μM compound (grey) overlaid on starting fragments (yellow).

Round 1 Synthesis and Enamine Similarity Search

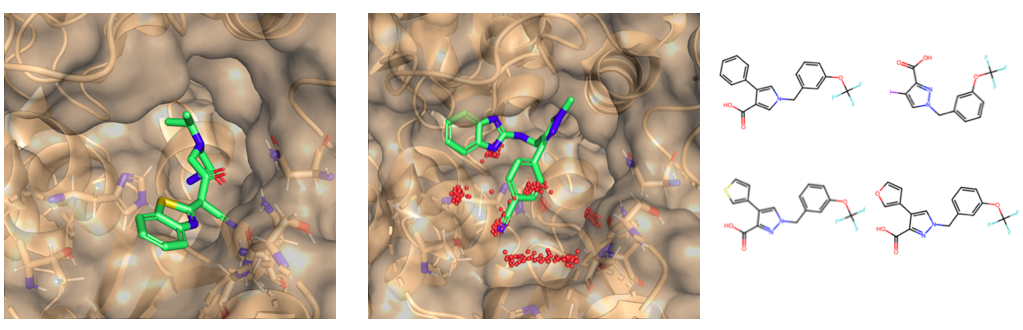

Following the design stage, we submitted around 100 compounds for experimental testing. Compounds were selected from similarity searches of the Enamine database. The catalogue was filtered by Tanimoto similarity between the Morgan fingerprints of the database molecules and our designed hits, and then by additional physical properties (such as molecular weight). Finally, the the purchasable compounds were re-docked using the gnina software.

Some compounds followed our general design strategy (e.g. see Figure below, left), following re-docking, others adopted alternative binding modes, such as sitting in the R2 pocket (e.g. see Figure below, centre). We attempted to choose a varied selection of each for purchase.

To more directly test our fragment growing strategy, the medicinal chemistry team also synthesised four compounds in-house and submitted them for testing.

(left) Top-scoring compound according to the docking score. (centre) Docking pose of our Round 1 hit compound. (right) Compounds synthesised in-house.

Round 2 Model Refinement

Compounds were tested by the challenge organisers for aggregation and solubility, and for binding to NSP13 using a SPR assay. Based on these properties, one of our compounds was selected for advancement to round 2 (in total, 46 compounds selected by 18 participants progressed).

We carried out a further round of hit expansion via a substructure search of the Enamine REAL database, based on our hit compound. The resulting library of compounds was re-built into the NSP13 binding pocket using FEgrow, and scored.

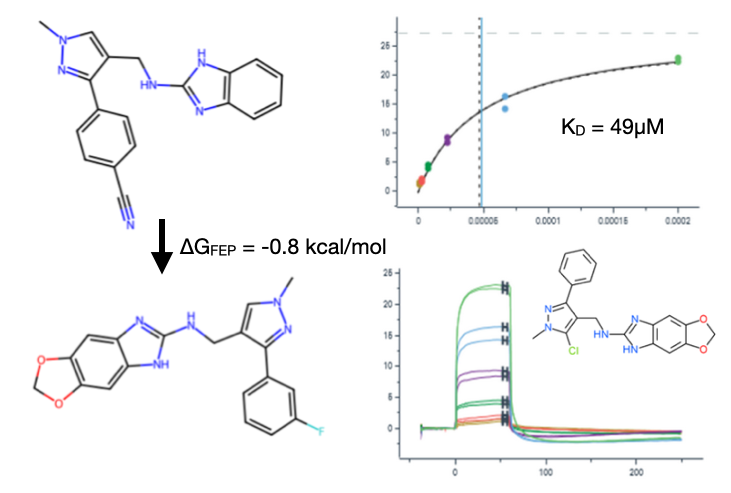

A series of eight promising analogues was further investigated via free energy calculations using the BioSimSpace package. Of those, the majority had similar predicted binding free energies as the original hit, except for one dioxolane analogue (see below), which showed promise. Pleasingly, a similar compound was verified experimentally (see data below).

Overall, four of our compounds in round 2, including the re-supplied parent molecule, showed a binding response by SPR with a tendency to reach saturation (measured KD between 49 and 124 μM).

Round 2 free energy data and example experimental confirmation.

What we learned

Our combined normalised sum of all scores from members of the hit evaluation comittee, based on biophysical properties as well as medicinal chemistry evaluation, placed us 9th out of 22 participants (see here). Also of note, we finished first on a secondary evaluation metric, in which we attempted to classify a merged list of all participants’ selections as binders/non-binders.

More importantly, the opportunity to get involved in a prospective hit-finding campaign taught us a lot about what worked and what needed improvement in our workflows:

- Manual growth with FEgrow is useful for idea generation, but automated searches are needed on a tight deadline.

- More accurate scoring of binding poses is always needed (everything we suggested was predicted to be low micromolar or better).

- Free energy calculations proved to be useful here in round 2, but we need more compute resource (or faster FE calculations) to drive the design process.

- The similarity between our compound designs and those available in chemical databases tended to be low, although the purchased compounds did generally recover many of the binding modes that we were targeting.

- Usually we work with multiple rounds of structural biology, and having that extra information after round 1 would (we think) improve hit rate a lot.

- Regular input from experienced chemists and biologists is crucial to keep our designs on track (thanks Roly, Kate and Natalie!).

Indeed, based on this experience, we have subsequently made a number of improvements to FEgrow to enable active-learning driven compound design, with custom scoring functions and automated seeding of molecules available from on-demand chemical libraries (check out our recent preprint for details).